Jack Neely, Knoxville History Project

Happy Holler has its origins in the 1880s, when Brookside Mills, the large and progressive fabric-weaving operation, opened along the railroad tracks and Second Creek just west of Central, soon to become one of Knoxville’s largest and most admired factories. The specialty weaving mill produced premium and. complex fabrics, like corduroy and velvet, and employed more than a thousand. Before the proliferation of automobiles, its employees, both management and labor, mostly lived within walking distance of Brookside, and a commercial section along Central evolved to serve them.

Brookside was in what had been a rural area outside of city limits. North Central’s Happy Hollow was never considered part of the city until an annexation in 1897, and for the next 20 years, it represented the northwestern outskirts of Knoxville.

Happy Holler (or Hollow, as it was more often spelled, regardless of pronunciation) seems to have become a familiar if informal name for the low-lying area between Scott and Baxter Avenues by 1899, when a short news article about the new location of Irish immigrant Dan Kavanaugh’s saloon describes “Happy Hollow” as a place on “North Central Avenue, between Brookside and Anderson streets.”

By one credible story, it was a road problem, a treacherous dip near Anderson Avenue, that sparked its reputation for nightlife. An Irish immigrant named Dan Kavanaugh, who had run saloons in the Irish Town area of Knoxville for years, noticed that farmers’ wagons coming into town would often have trouble at the bottom, along Anderson Avenue, and get bogged down in mud, or perhaps break a wheel or an axle. To him, it looked like a great place for a disgruntled farmer to take a break and have a beer, and tarry there while figuring out what to do.

He opened his saloon on the 1100 block of Central by early 1899, and named it the “First and Last Chance” presumably because it was the first saloon encountered by southbound visitors, and the last encountered by northbound visitors. Unfortunately, he didn’t get to enjoy that advantage for long. In October 1899, Kavanaugh died after a brief illness. His wife, Texana, took over, with help from her brother, William Chamberlain, who ran the saloon for some years, sometimes getting in trouble for selling whiskey on Sunday. A second saloon, opened by another Irishman named William Mournan, opened across the street a few years before saloons were formally banned in Knoxville in 1907.

During Prohibition, Happy Holler developed a reputation for bootlegging, generating stories of a complex whiskey underworld that are hard to prove or disprove.

***

Among those attracted to work at Brookside were the Larkin Brown family, who arrived around 1901. Although previously based in Massachusetts, Larkin and his wife were from Georgia and Ireland, respectively. An able manager, Larkin Brown rose in Brookside’s ranks, and became plant manager, as his family moved into progressively larger homes along Central, the last on East Scott Avenue. Their son, Clarence, lived in the Happy Holler area for about a decade, during which time he attended Knoxville High School and the University of Tennessee, from which he graduated in 1910, with a graduate thesis about improving efficiency at his father’s Brookside Mills. He would become a major filmmaker in Hollywood between 1920 and 1952. Some of his movies, especially the unusual comedy Ah, Wilderness (1935) include Knoxville touches. It’s not proven whether some of his famous speakeasy settings, like Greta Garbo’s bar scene in Anna Christie (1930), were informed by memories of Happy Holler.

Over the years, as Brookside grew, so did other industries, especially the Coster Shops, which opened in 1906, a few blocks to the northwest; named in memory of Charles Coster, a close associate of financier and railroad tycoon J.P. Morgan, the major facility was the Southern Railway’s primary national train repair center, employing almost 2,000 in its early days. Among Happy Holler’s early clientele, many were railroad men.

The adjacent neighborhood of North Knoxville became more populated, with both large houses and very small ones. Happy Holler was a commercial district that answered practical needs for working people, with groceries, barber shops, cobblers, bakeries, meat markets, service stations, and drugstores.

Many of Knoxville’s Irish-Catholic families, previously crowded in old Irish Town a few blocks to the southeast, moved into the newer neighborhoods, with freestanding houses and yards for trees and gardens. Their church followed them. The first Holy Ghost Catholic Church—only the second Catholic church established in the Knoxville area—opened in 1908. That church building remains, as one of Happy Holler’s oldest works of architecture, even though it was replaced in purpose in 1926 with a much larger church to stand beside it.

In 1917, Happy Holler had its own movie theatre, showing silent films; the Picto, later known as the Cameo, finally known as the Joy Theatre, lasted almost 40 years. A sandlot baseball team was known by 1926 as the Happy Hollow Tigers, but Brookside also boasted of its own baseball team.

After beer was re-legalized in 1933, Happy Holler embraced the new liberty, even if most young patrons didn’t remember Kavanaugh, Chamberlain, Texana Long, and the saloon era. Whiskey remained illegal, though, so Happy Holler’s bootlegging reputation prevailed for some years to come, and with it, a reputation for targeted violence, though many neighbors have insisted it has been inflated in the popular imagination.

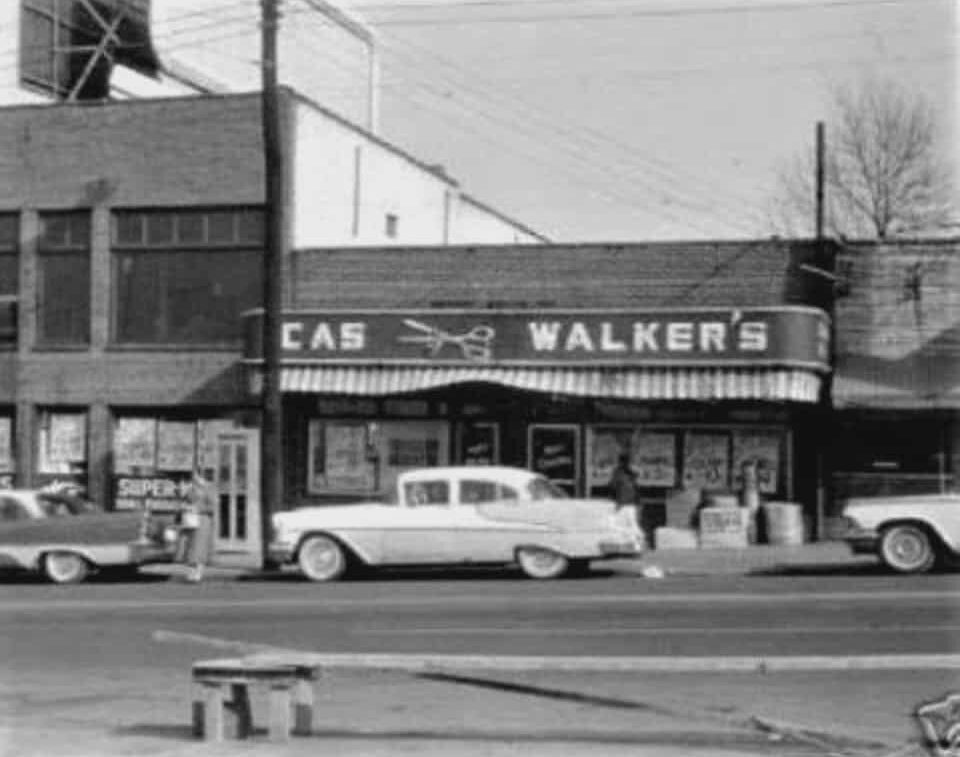

Happy Holler was also associated with some legal businesses, notably bakeries, like Sanitary Bakery, there before 1920, which evolved into American Bakeries, and Merita. Flamboyant groceryman Cas Walker ran an “open-air market” on the 1100 block of North Central by 1936, claiming to keep it open 24 hours a day.

A new industry opened nearby to the northwest in the late 1930s: the Dempster Dumpster plant, the world’s first factory to manufacture the patented Dumpster, unveiled in 1936 by George Dempster, another industrial boost to the neighborhood.

Sears-Roebuck built a modern suburban-style department store on the hillside overlooking Happy Holler, in 1947, the first in a series of radical changes. Sears was Knoxville’s first large store ever built outside of downtown, and the first with a dedicated free parking lot. It was arguably the beginning of the suburbanization of Knoxville’s core commercial district. (The Freezo, the snack shop that would quickly become a Happy Holler institution, opened about the same time.)

Brookside Mills, the original impetus for Happy Holler’s development, closed in 1956. In 1960, the construction of I-75 (later known as I-275) demolished almost 500 homes by eminent domain, reducing the walking clientele of the old commercial district. Much of the old grocery trade dwindled.

By the 1960s and ‘70s, Happy Holler was becoming famous, or infamous, as a sketchy entertainment district, hosting several late-night bars, some of which had worse reputations than others, as well as poolhalls, a boxing ring, and Niceley’s Package Store. Some were proud when national radio personality Paul Harvey reportedly mentioned the neighborhood, describing a brutal murder that happened “in the Friendly Tavern in Happy Holler.”

Not just a lively place to visit, Happy Holler was home to several notables. Howard Bozeman, who grew up on Baxter Avenue, and came to know the Holler as a paperboy, became an especially influential county judge and civic leader in mid-century Knoxville. Carl and Pearl Butler, who lived here for a time, were known on Knoxville radio in the 1950s, and became major stars in Nashville in the 1960s. D.D. Lewis, who grew up in 1950s-60s Happy Holler, known as a football player for Fulton High School, later saw several Super Bowls as a formidable linebacker for the Dallas Cowboys.

In the early 1970s, Big John Tate, Knoxville’s most internationally celebrated boxer, trained at an upstairs boxing ring associated with Porky’s Sports Center, at the northwest corner of Central and Anderson. The Olympic bronze medalist became the World Boxing Association’s Heavyweight champion in 1979-80.

Happy Holler was considered a civic problem, especially in 1982 when an unsolved double-murder behind a bar underscored the district’s old violent reputation. Sears closed in 1984. Huge old Brookside Mills, which had seen some other uses as warehouse space, was finally demolished in a months-long process in 1996-97.

But a few businesses, including the ca. 1948 Freezo, remained and thrived, and as Old North revived as a historically preserved and popular neighborhood, it became obvious that there was new potential in old Happy Holler.

In 2002, a member of an old Irish family from the neighborhood, Dan Moriarty, opened the unique Time Warp Tea Room, drawing new interest in a new-urbanist era. Happy Hollerpalooza, a neighborhood- centric street far, launched in 2005, the brainchild of the family that ran Friends Antiques and Collectibles. By 2008, Happy Holler’s potential had gotten the attention of the City of Knoxville, which included it in its Downtown North Redevelopment initiative. Relix Variety Theatre welcomed an unusual three-week residency by internationally adventurous banjoist Abigail Washburn in late 2010; the first annual mini-music-festival benefit known as Waynestock debuted in the same venue in early 2011. By the time the expansive restaurant Central Flats and Taps opened later that year, it was clear that Happy Holler was back to stay in a new century. The 2017 launch of Central Cinema, an offbeat movie theater in the same space once occupied by neighborhood theaters the Picto, the Cameo, and the Joy, affirmed the historical continuity of the neighborhood, and its place in modern Knoxville’s culture.

An evening with the winemaker 🍷

Join @zerozeroknox on February 5th from 6–9pm for a by the glass takeover featuring Guthrie Family Wines. Meet the winemaker, sip something special, and let DJ Derek O Martin set the mood with vinyl selections all night long.

It’s better in the Happy Holler. ✨

The most vibrant spot in Happy Holler🌈

@chopshophair is more than a salon; it’s a warm, creative hub where comfort, artistry, and community collide.

Got a song up your sleeve? Jump on stage and play, they’ll reward you with a discount.

Everything’s better in the Happy Holler.

Waynestock is back for three nights of live rock ’n’ roll at @relix_brookside_knoxville in Happy Holler.

Featuring a lineup of local favorites and fresh faces, this all-ages event blends great music with a greater purpose. This year’s proceeds benefit Centro Hispano and their Family Preparedness and legal clinic programs serving Knoxville families.

$10 entry, raffle prizes, and a weekend built on community.

It’s better in the Happy Holler.

Rooted in tradition and blooming in Knoxville.

@_stemtostem_ is Happy Holler’s go-to for same-day delivery of beautifully handcrafted floral arrangements—thoughtfully designed for everything from heartfelt sympathy tributes to joyful, everyday bouquets.

It’s better in the Happy Holler.

A perfect Friday evening, poured.

Tonight, @centralbottleknox hosts a special tasting with PJ Rosenberg of @vomboden. Thoughtfully crafted wines and a great way to start the weekend.

It’s better in the Happy Holler.